Look around, and you’ll find GIS everywhere – in obvious and less obvious ways. From Google Maps to air traffic control, from parcel tracking to land use analysis, geographical information systems have come to underpin every major aspect of our economy, including oil and gas. GIS is no longer a standalone concept or system, it’s a geospatial way of working that has firmly embedded itself in our lives.

This poses a curious challenge for geospatial practitioners and users alike.

In a world where technical constraints are falling away – live streaming from Mars, anyone? – it may ironically seem harder to find specific solutions to specific problems. This is because, freed of technological barriers, you’re now forced to evaluate what the actual problem is that you’re trying to solve. This is quite different to being presented with, say, pipeline profiles or moving vessels on a map, and then decide whether or not any of these specific solutions might be useful to you.

Today you can update a map on an iPad whilst sitting on a boat in the middle of the ocean, and ten seconds later your colleagues half-way round the world can annotate that same map with a freehand doodle and send it back to you before you’ve had a chance to lose your tablet overboard.

But – just because you can, should you? Before we try to answer this question, let’s take a quick look at some of the recent trends in the realms of GIS.

An ocean of data

The world is now awash with data. What’s new is not really ‘big’ data, but how easy it has become to create, share and consume data – anywhere, on any device, using a wide choice of geospatial apps.

For a start, there is now a plethora of public and volunteered (crowd-sourced) datasets freely available, enabling you to quickly build up a quality basemap for any use case and spend more time on data analysis, not data gathering. There’s literally thousands of examples, from the fantastic basemaps of Natural Earth to the global Geonames.org gazetteer, from the iconic Landsat earth observation programme to elevation or environmental data, from mineral resources to oil & gas data provided by national governments.

But if you’re an ArcGIS user then look no further than ArcGIS Online, a veritable treasure trove providing thousands of ready-to-use datasets from both official sources and the ArcGIS user community – including most of the free sites found elsewhere. From global bathymetry to world heritage sites, it’s also fully integrated with ArcGIS so you don’t even have to store or update the data locally, saving you time and money.

Managing the data deluge

As more data sources are coming online the traditional model of centralised data management is rapidly evolving, and may even become obsolete. Why store everything in one place when people can simply pull in web feeds as and when needed?

This has major ramifications for organisations looking to take advantage of what’s on offer. Whilst GIS should now be cheaper to run and more effective to use than ever before, many organisations however still struggle with their own internal data management – especially as people can now generate and share data at blistering speed.

There are currently two schools of thought on how this data management challenge can be tackled in the future. On the one hand, the thinking goes that advances in artificial intelligence and smarter search tools should automate data management, making human intervention obsolete. You may have noticed, for example, that Google does not ask the internet to clean up or restructure its pages so they can be searched and classified. There is no reason the same can’t apply to other data. On the other hand, there is a view particularly in the E&P industry that proper data management will always require human input and expertise, and so we should just bite the bullet and make the necessary investments in people and processes.

We probably need a bit of both, together with a realisation that data will never be perfect.

GIS as a platform

As data becomes more widely distributed it also changes the very nature of GIS, and how it is used. Gone are the days when people were chained to their GIS desktop as the only outlet of spatial data. As GIS has gone mainstream many non-GIS apps now have geospatial functions built into them too – not just heavy-duty geoscience, statistical or business intelligence software, but also simple things like weather maps or mobile apps.

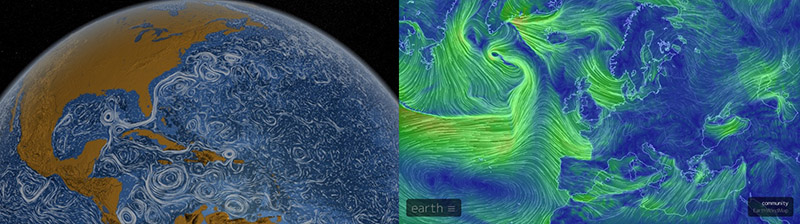

People have become more geo-literate. And the intersection of geospatial and other worlds – such as art and design – can produce stunning results (my personal favourites include Earth Wind Map and NASA’s Perpetual Ocean).

NASA Perpetual Ocean (left) and Earth Wind Map (right): Two data visualisation examples that are even more mesmerising live as a moving map display.

NASA Perpetual Ocean (left) and Earth Wind Map (right): Two data visualisation examples that are even more mesmerising live as a moving map display.

In the old days we had heavy doses of GIS concentrated in few places, but now everything is getting covered with a light sprinkling of geospatial seasoning. The result is that GIS is becoming more decentralised, pervasive, and nebulous – yes, more cloud-like. In other words, GIS is turning into a ‘platform.’

The best way to describe this is to think of GIS no longer as the single silo that stores and analyses all the world’s spatial data, but rather as a collection of distribution centres that take delivery of and dispatch spatial data to and from any location. These distribution centres may include anything from web maps to mobile phones or even smart fridges (the so-called “internet of things”). Of course, the single GIS desktop still has its place for dedicated GIS professionals, but it’s no longer the geospatial fortress it once was.

The GIS platform means that anybody, anywhere, can now perform GIS tasks on any device. And most importantly, it is now all connected over the web such that data can be updated and synchronised in real-time, eliminating duplication of effort. Why create your own basemap when you can simply pull in a better one via the web? Why spend hours formatting and processing data when the same thing has already been done by someone else? Why spend hours updating maps on the screen when your field staff can do it themselves in situ?

This gives web-based GIS a new, central role – not the clunky, pre-defined web map it once was, but the go-to place for map feeds and services that allow people to consume, manipulate and share spatial data in any way they like. We’re about to reach a level of technical maturity where anything goes.

Which brings us back to my earlier point.

Figuring out what to do

In a world where everything is possible, it’s more important than ever to first consider your true needs before looking at technical solutions (which is why I’ve deliberately not mentioned any in this article). At the end of the day, GIS has to either save you money, increase your returns, or make you more productive – if not, something’s gone wrong.

As a GIS consultant I sometimes spend surprisingly little time on GIS. Contrary to what clients might expect, my advice is usually not to rush into solutions. Instead, we first spend some time defining the problem. This is an investment that repays itself many times over once the project is delivered. It sounds a lot more trivial than it is, as often the problem needs reframing before it can be tackled successfully. When, for example, geologists say they are able to spend only 30% of their time on geology, it pays to consider what problem GIS is exactly supposed to solve. No map gizmo, however sexy, will make much of a difference unless it also addresses the other 70%. Once the problem is clearly defined, the solution basically designs itself. And implemented correctly, it will deliver measurable results and benefits.

The oil and gas industry may be facing tough times, but with GIS being faster to implement and easier to use than ever before, the time has never been better to re-evaluate how it could help you grow out of the downturn.

Sorry, did I just mention a solution?

Written by Thierry Gregorius, Principal Consultant, Exprodat.

Image credits:

Robot by Peyri Herrara on Flickr.com (Creative Commons).

NASA Perpetual Ocean http://www.nasa.gov/topics/earth/features/perpetual-ocean.html (public domain).

Earth Wind Map http://earth.nullschool.net/ (open source).

Upside-down house by Alexander on Flickr.com (Creative Commons).